8. Members of Zion 21.0 would participate in the world economy.

Modern goods and services.

Members of Zion 21.0 would want most of the goods and services available in 21st-century developed economies. They would not live like people in Abraham’s time, or even Joseph Smith’s time. They would have far more than the minimum needed for food, clothing, shelter, and some books.

Modern technology is a mixed blessing, but a blessing nonetheless. For the pure in heart in Zion 21.0, the ability to retrieve vast amounts of information, communicate easily with people in distant places, and travel rapidly would help them in gaining knowledge and wisdom and in serving people around them. They would not want to trade current conditions for a life likely to last only half as long, beset with illness and disability.

Using the best and most appropriate technology available, members of Zion 21.0 would seek material abundance and prosperity. The Book of Mormon often repeats the promise that if the people would keep the Lord’s commandments they would “prosper in the land” (e.g., Alma 50:17–20), which includes material prosperity. The righteous people of Zion would “seek for riches” without worshipping them as false gods.* They would use abundance to bless their own lives and do good for others.

_____________________________

* See Jacob 2:18–19; 2 Nephi 9:30; Spencer W. Kimball, “The False Gods We Worship,” Ensign, June 1976, 3–6, available here.

Zion 21.0 would not be able to produce on its own everything its members would want to purchase.

There are many reasons why an economic unit of the size of Zion 21.0 would not be able to produce on its own all the goods and services its members would want to purchase.

1. In the modern world, no community lives in isolation. Much of what we consume comes from producers located at a considerable distance. Even local producers rely on inputs that they do not produce themselves but rather purchase from other suppliers, which are often distant.

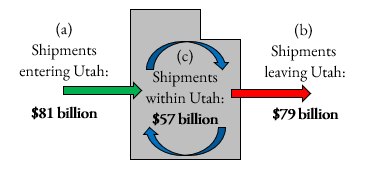

The state of Utah can illustrate this point. Many more goods are shipped into Utah from outside the state than are shipped within Utah. Similarly, many more goods are shipped out of Utah than are shipped to destinations within Utah. Even if Zion 21.0 were as large as the state of Utah, it would not come close to producing all the products it consumes or using all the products it produces. Trade with the rest of the economy would be essential. (Note that Utah is a typical state in this regard.)

2. A relatively small area (or areas) such as Zion 21.0 would not be able to manufacture many of the products its members would want to consume. Utah can again serve as an example. The United States Census Bureau classifies manufacturing into 360 categories based on the type of activity. Of these, Utah had no reportable production in 144 industries, 40 percent of the total.

Some of the “missing” industries produce consumer goods, including breakfast cereal, seafood products, sugar, socks, footwear, electric lamp bulbs, electrical appliances, paper, cars, and trucks. Other “missing” industries produce products normally used by businesses in their own production processes, such as synthetic fibers, printing ink, iron and steel, railroad vehicles, and several categories of fabrics. Even within the remaining 216 industrial categories, there are many products that are not produced in Utah. An economic unit as large as a U.S. state does not come close to manufacturing all the products it consumes. It is implausible that Zion 21.0 could produce on its own everything its members would want to purchase.

3. If Zion 21.0 had no trade with the rest of the world, it would have limited access to resources. Again, take Utah as an example. Utah does not have deposits of bauxite (the ore from which most aluminum is produced), cadmium (used in NiCad batteries in many electronic devices), or gallium (used in integrated circuits and LED lights). If there were no commerce with the outside world, aluminum, NiCad batteries, and integrated circuits could not be produced in Utah. This could also be true of some agricultural goods, such as bananas or rice that are not now grown in Utah. In some cases, it would be relatively easy to substitute other goods that can be produced in Utah, but in other cases, it would be very difficult. The same would be true for Zion 21.0.

Belief that Zion must be totally separate from the world’s economy is misguided.

Hugh Nibley was a prominent advocate for the view that Zion cannot have anything to do with the world economy. This is a dominant theme in his book, Approaching Zion.* For instance, Nibley maintained, “Like the people of Lehi and the primitive Christians, the Latter-day Saints were asked and forced to make a clean break with the world—‘the world’ meaning explicitly the world’s economy” (Approaching Zion (“AZ”), 342-43). “The world as we know it is the very antithesis of Zion . . . . No one is more completely ‘of the world’ than one who lives by the world’s economy, whatever his display of open piety” (AZ 248).

Nibley’s view that Zion must have nothing to do with the world’s economy and the principles under which it operates does not seem to square with the efforts to establish Zion in the 1830s. Zion included the United Firm, referred to in the Doctrine and Covenants as the United Order. The United Firm comprised the Literary Firm, responsible to publish and sell the revelations, and the Mercantile Firm, which operated stores in Ohio and Missouri.** These business interests included an ashery, which produced potash that was sold to non-Latter-day Saint buyers.*** As other members of Zion operated their stewardships, “the profit system, the forces of supply and demand, and the price system” guided decisions on what to produce and how to produce it.†

For Zion 21.0, participating in the world’s economy would mean selling goods or services outside of Zion and buying goods or services produced outside Zion. In Zion 21.0, what most households would have to sell is labor services. Most adults within certain age ranges would work for and be paid by non-Zion employers. Of course, a job that requires a person to take advantage of others, to harm others, or to be anything other than totally honest is not a job that a pure in heart Zion member could take. Nibley seems to believe that most jobs in the world’s economy encourage or even require actions that are less than upright. “Anyone knows that cheating pays off very well in this country” (AZ 445). “Inequality comes from dishonest men with ingenious plans, who endanger ‘the Rest’ by forcing all to play the game their way to avoid becoming their victims” (AZ 372). In fact, there are abundant opportunities for honorable employment.

Nibley seems to misunderstand the nature of activities in the world’s economy. For him, one person’s gain is achieved only through another person’s loss. “Competitiveness always rests on the assumption of a life-and-death struggle . . . . The name of the game is survival” (AZ 460). He repeatedly cites Cain as the archetype of economic activity. “Satan approached Cain and taught him the basic principles of business” (AZ 435; see also AZ 17, 166). After Cain killed his brother Abel to take his flocks, “his murder didn’t bother him in the least. Thus when the Lord asked him, ‘Where is your brother Abel?’ Cain said, ‘that is none of my business; he can take care of himself. If not, that is just too bad for him—he deserves what he gets’ (cf. Moses 5:34). It’s a dog-eat-dog world, says the entrepreneur . . .” (AZ 436).

In truth, the nature of economic relationships is not taking from others. Economic relationships are fundamentally about making an exchange in which both parties benefit. In the vast majority of cases, both parties to a transaction receive something that they value more highly than what they give up. When a person purchases a dish of ice cream for a dollar, he does so voluntarily because he would rather have the ice cream than have the dollar. Under other conditions (say, it is cold outside, or he is on a diet), the ice cream is not worth a dollar to him, and he does not buy it. Similarly, the ice cream shop would generally be unwilling to trade the dish of ice cream for a dollar if it costs more than a dollar to make or acquire the ice cream. The very fact that a voluntary exchange took place shows that the exchange was beneficial to both parties.

There are certainly businesses that deliberately deceive their customers or mistreat their employees or suppliers. However, most businesses try to provide goods and services to satisfied customers who will return to make other purchases and recommend the business to their friends. Businesses that cannot consistently do this generally close after a while.

There are plenty of incentives for individuals who work in business to behave well. Customers, suppliers, and co-workers are inclined to work and cooperate with those who behave well, and they try to avoid relationships in which they are treated badly. Honesty, taking responsibility, and fairness are all virtues that are valued in the world’s economy. Of course, people do not always live up to high standards. There can be both opportunity and motive to lie or misrepresent, to do less than one promised to do, or to take advantage of others. But it is certainly not true that a person in business must behave badly. Furthermore, the opportunity to sin is not unique to business. There are temptations in any work environment, just as there are in virtually every human interaction outside of work. One can lie to a neighbor, deceive a Church leader, or break a promise to a loved one. It doesn’t make sense to avoid the world’s economy merely because a person can behave badly there, since the same logic would force us to avoid all social interaction.

_____________________________

*† Hugh Nibley, Approaching Zion, (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, in cooperation with Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1989).

** Max H Parkin, “Joseph Smith and the United Firm: The Growth and Decline of the Church’s First Master Plan of Business and Finance, Ohio and Missouri, 1832–1834,” BYU Studies 46, no. 3 (2007), 9, 13–14. See also Doctrine and Covenants 57:8 and 63:42 directing Sidney Gilbert to establish and Newell K. Whitney to retain a store.

*** Karl Ricks Anderson, Joseph Smith’s Kirtland: Eyewitness Accounts (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 132–33; Benjamin C. Pykles, “An Introduction to the Kirtland Flats Ashery,” BYU Studies 41, no. 1 (2002), 176, 179.

† Leonard J. Arrington, Feramorz Y. Fox and Dean L. May, Building the City of God: Community and Cooperation among the Mormons, 2nd ed. (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 17. See also Lowell L. Bennion, An Introduction to the Gospel (Salt Lake City: Deseret Sunday School Union Board, 1955), 281. Under the 1830s system of consecration and stewardship, “business operations were to proceed under a free enterprise system.”