6. Equality would be adjusted for needs and circumstances.

“Wants” and “needs” were two terms for the same concept.

Doctrine and Covenants 51:3 directs that households in Zion are to be equal “according to [their] circumstances and [their] wants and needs.” As we use these words today, “wants” and “needs” have different and contrasting meanings. For instance, a budgeting counselor may might urge a household focus on “needs” (the things that a family must have) and only meet “wants” (the things the family desires to have but can do without) if there is money left over.

However, when the revelation that became section 51 was given in 1831, the words “want” and “need” were not contrasts: they were two words for the same concept. Noah Webster published his American Dictionary of the English Language in 1828. He listed multiple definitions for the noun “want.” The first four were as follows:

- Deficiency; defect; the absence of that which is necessary or useful.

- Need; necessity; the effect of deficiency.

- Poverty; penury; indigence.

- The state of not having. (American Dictionary of the English Language), available here.

A “want” was something that was lacking. Webster even used the word “need” in defining “want.” A definition of “want” similar to our current usage did not appear until the fifth definition: “That which is not possessed, but is desired or necessary for use or pleasure.” Similarly, Webster used the word “want” to define the noun “need.”

- Want; occasion for something; necessity; a state that requires supply or relief. It sometimes expresses urgent want; pressing exigency.

- Want of the means of subsistence; poverty; indigence. (American Dictionary of the English Language), available here.

In the Doctrine and Covenants, words with identical or very close meaning are used together in dozens of passages, perhaps for emphasis.

Other scriptures revealed in or translated into English at about the same time as section 51 also use “want” to mean something that is needed or lacking.

Other writings from the early part of the nineteenth century also distinguish between “want” and “desire,” rather than equating them as we would in the 21st century.

When these terms are properly understood, there is no suggestion that income in Zion 21.0 would be apportioned based on desires. We live in a condition economists call “scarcity,” where what we desire is greater than what can be produced with the limited resources available. While we may be satisfied with what we have, there are few people who would not prefer to have more of something than they have. It is impossible to give to everyone all that they desire, since our desires are basically limitless. Equality in Zion 21.0 would not dictate that two households receive different incomes because one has a greater or more intense desire for goods and services than the other. Rather, incomes would differ from household to household based on recognized needs.

Household size.

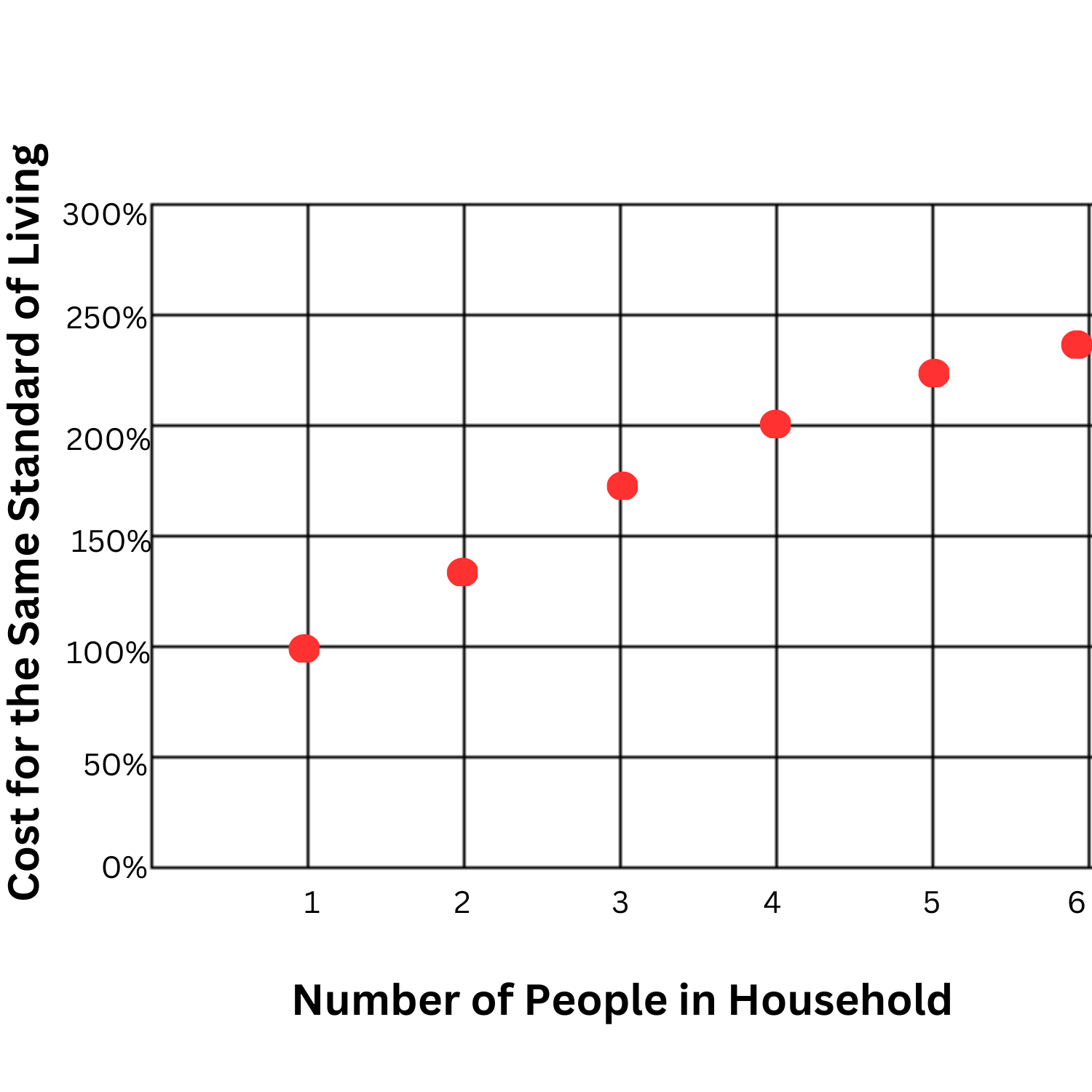

The cost of providing a certain standard of living for everyone in a household increases as the household gets larger. But the increase is not proportional to the increase in household size. Two can’t live as cheaply as one, contrary to the popular saying. However, they can live more cheaply together than they could in two separate households. For instance, needs for housing space or electricity are not twice as high for a household of two than for a person living alone. If the household size doubles again to include four people, expenses will not double.

A larger household has greater need than a smaller household, but how much greater? One commonly used method assumes that expenditures to maintain a standard of living increase with the square root of the number of people in the household. This means that, starting with a base level of what one person would spend, a two-person household would have expenditures of about 1.4 times the base level, since the square root of two is approximately 1.4. Similarly, a three-person household would have expenditures of about 1.7 times the base level, and a four-person household would have expenditures about double the base level. Other methods take account of the age of household members. In Zion 21.0, an equivalence scale like this would be used to calculate income adjustments for differences in household size.

More information on equivalence scales is available here.

Cost of living.

Income equality in Zion is intended to give all households the same ability, adjusted for need, to purchase goods and services with which to seek heavenly things. Imagine two Zion households, the Abbots and the Bakers, with the same needs (e.g., both households have the same number of people of the same ages). These two households might be provided with the same income in Zion, but they may still not be equal in their ability to purchase goods and services if they live in different places. Specifically, local price levels, also referred to as the cost of living, may differ between the two locations. For instance, if a household in Utah spends $4,000 to purchase a “basket” of goods and services that a typical household would buy, a household would spend about $4,700 in California and about $3,700 in Mississippi to purchase the same goods and services. Such different circumstances would call for an income adjustment.

Data on the cost of living in different cities and states in the United States are available here. Data are also available to adjust for international differences in the cost of living. Search for “PPP Conversion Factor, Private Consumption” here. The Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) conversion factor is the number of units of a country’s currency needed to buy the same quantity of goods and services in that country as $1 US would buy in the United States.

Taxes.

Imagine two Zion households, the Coopers and the Drapers, that have the same needs and receive the same equalized income. Due to circumstances, the Coopers are required to pay more in taxes than the Drapers. The two households are not equal: after paying taxes, the Coopers would have less money to purchase goods and services they want than the Drapers. To maintain equality, Zion 21.0 would make adjustments for the circumstance of taxes.

One reason the Coopers may owe more taxes is that they have higher wage or non-wage income than the Drapers. Another reason is that households may be taxed different amounts because of where they live. For instance, in the United States, state income tax rates and sales tax rates differ from state to state.

To adjust for taxes, the Storehouse could set aside money equal to the estimated taxes of Zion households. Households would report to the Storehouse their actual federal and state income taxes along with their earnings and non-wage gains. The Storehouse would then use the set-aside funds to reimburse each household for the taxes it paid. The Storehouse would also reimburse for estimated sales taxes. In effect, the Storehouse is equalizing after-tax income levels.

Healthcare.

The need for health care differs across households with different illnesses, injuries and chronic conditions. Even households with the same health conditions will spend different amounts on health care because they have different health insurance, or no insurance. In addition, the portion of health insurance costs paid for by employers and the government differs across households. Zion 21.0 could decide to reimburse all households for their health care expenses.

Education.

Households with school-age children and youth have a greater need for education. Zion 21.0 would decide what level of education should be provided to all its members. For instance, members of Zion may want all their young people to receive primary and secondary education (“high school” in US terms) and, say, up to four years of academic or vocational training beyond high school.

Adequate basic education through high school is provided by the government in the United States and many other countries. In this circumstance, Zion households with school-age children have a need for schooling but do not require any income adjustment. Similarly, for some students and in some states and countries, two or even four additional years of academic or vocational training are also available at little or no cost to the household. However, in circumstances where a young person incurs a considerable cost to get post-secondary education, the household would receive an income adjustment to cover the cost. The Storehouse could make payments directly to the school or reimburse the household’s expense.

Some differences between households would not result in income adjustments.

In Zion 21.0, more income would be distributed to households with greater needs so that those needs can be filled. A family with more mouths to feed gets more income to purchase food. If a household member has a disability or health problem, that household receives more resources so it can reduce or eliminate the disability or health problem. In short, where there is something lacking, Zion attempts to supply what is lacking.

This is not the same as trying to compensate an individual or household for what it lacks. One could list many conditions that might make it more difficult for a person to obtain heavenly things. For instance, lacking a spouse could hinder someone in learning the lessons that marriage offers. Similarly, a person with few friends, or one who grew up without affectionate or supporting parents, or one who finds less beauty in life because he is color-blind or tone-deaf, might face some disadvantages in seeking heavenly things. However, additional income cannot provide what is lacking. One cannot purchase a spouse, friends, a happy childhood or (at least with current technology) the ability to distinguish colors or melodies. Zion equality does not call for extra income that the person can spend on something else in the hope that it will somehow “make up” or compensate for some lack.

There are at least two reasons why such compensating income would not be a feature of equality in Zion 21.0. First, it is not humanly possible to determine what experiences money can buy that would be equivalent to experiences a person has missed. For instance, who could say how much money should be provided for camping trips or visits to art museums that have a spiritual value equivalent to what a tone-deaf person would have received from hearing and appreciating music? Second, some precious things in life are altered and diminished when a price is attached. It is doubtful that we want to live in a world in which a friend is worth, say, $5,000 per year or the care of a loving parent is valued at $100,000 or $1,000,000 or any other level.